by Amythest Lee

April 1 marked the beginning of recreational crabbing season in Maryland. Picking crabs is a tradition for many Maryland families, and the blue crab is as synonymous with Maryland as the state flag and Old Bay.

Blue crabs, whose Latin name callinectes sapidus means “beautiful savory swimmer,” can be found in waters as far north as Nova Scotia and as far south as Uruguay. Despite this widespread range, blue crabs have always been closely associated with Maryland. It’s easy to see why — according to Maryland Department of Natural Resources, about 50% of crabs harvested in the United States come from Maryland waters.

Blue crabs, as their name suggests, have claws that are bright blue, with mature females sporting a bright red tip on each claw. They have a shell that varies in color from blue to olive green and is about 9 inches across. Blue crabs have three pairs of walking legs and a paddle-shaped swimming fin that can rotate 40 times per minute to allow them to stay in the water column.

Blue crabs are opportunistic feeders who eat a wide range of foods, including mussels, oysters, decaying plant and animal matter. Adult blue crabs sometimes eat juvenile blue crabs. They search for their food in the bay’s underwater grass beds, and these beds form a critical habitat that provides food, shelter and protection for younger crabs looking to avoid becoming a snack to a larger adult. It takes about 18 months for a blue crab to reach maturity and no longer have to worry about cannibalism from its older counterparts.

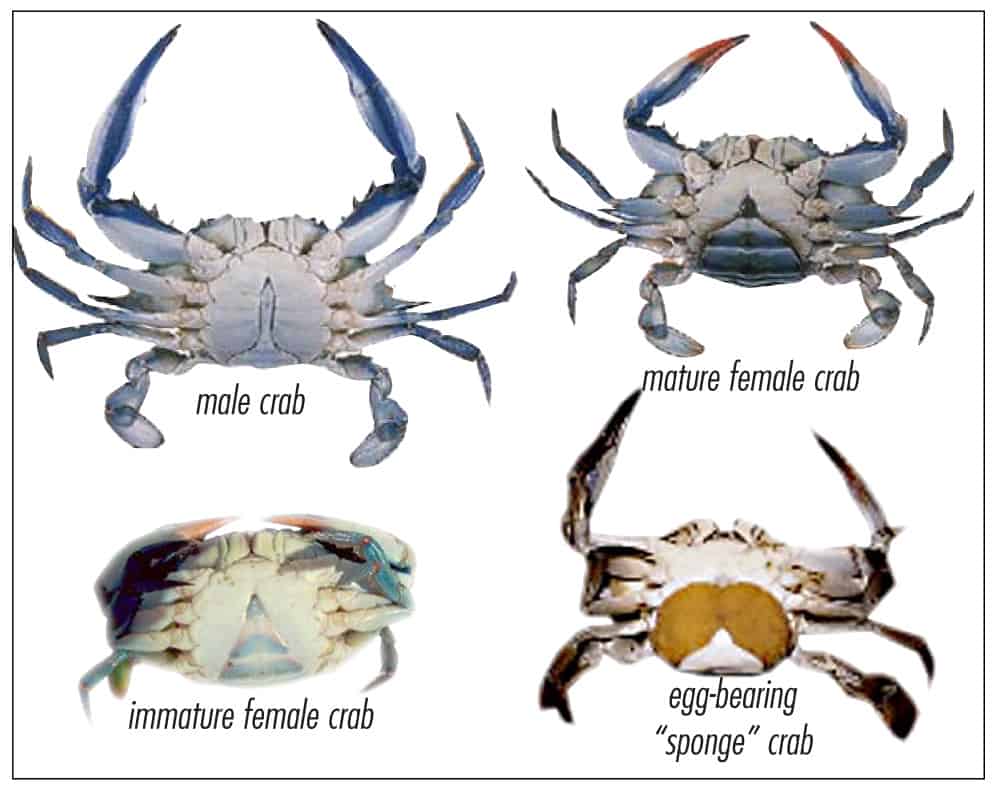

When observing blue crabs, you can tell the difference between a male and female by the size and shape of their apron, a flap on their underside. A female has what looks like the Capitol dome and a male has a thin, triangle-shaped apron similar to the Washington Monument.

There are different names for each type of crab. A “Sally” is an immature female; a “Jimmy” a mature male; a “peeler” is a crab about to molt; a “Sook” is a mature female; and a “sponge crab” is a mature female carrying a sponge-like mass of fertilized eggs on her abdomen that can hold up to 3.2 million eggs.

Why do Marylanders think our crabs are so special and taste so much better than other crabs when they can be found in such a wide range?

Experts believe Maryland’s four distinct seasons contribute to the delicate texture and buttery taste of our favorite crustacean. The crabs hibernate through the winter, which allows them to build up fat reserves called “mustard.” Connoisseurs say this provides a depth of flavor you won’t find in any other type of crab. You can tell a Maryland blue crab from other blue crabs by looking at the mustard. A blue crab from Maryland has a much darker shade of yellow mustard than other blue crab varieties.

During the off season, Maryland restaurants often use crabs from the Gulf of Mexico. Even during crab season, you might be eating crabs from out of state, as the bay doesn’t have enough to keep up with current demand. The easiest ways to ensure you’re getting Maryland crabs are to simply ask or by checking that the restaurant you’re visiting is True Blue-certified by the state of Maryland. This certification verifies that at least 75% of crabs or crabmeat used by the restaurant during the year come from Maryland.

Maryland blue crabs have been an essential part of the Eastern Shore diet for hundreds of years. This native species was plentiful and delicious, but quickly began to experience a decline in population due to overharvesting, especially when the crab pot was introduced in 1943. Climate change has also contributed to a reduction in blue crab population. Blue crabs make their homes in eel grass, and the plant has been experiencing damage due to recent warming temperatures in the bay. Climate change has also resulted in more severe storms, which dump sediment and pollution into the bay. This affects oxygen levels in the water and harms the bay’s wildlife — including blue crabs. Rising sea levels also threaten blue crab populations by destroying wetlands and shores along the Chesapeake Bay.

In 2008, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation created fishing guidelines to manage blue crab populations. They are also working to restore grass beds and oyster reefs, and created the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint in 2010, with the goal of significantly reducing pollution runoff from states in the Chesapeake Bay watershed by 2025.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation published a peer-reviewed economic report that estimated the economic value of implementing these practices will produce natural benefits of more than $22 billion annually.

These actions have already improved conditions in the bay. In general, the crab population has been doing well since the plan was agreed to in 2008. One of the best indicators of this increased abundance has been the fact that numbers have surpassed target abundance for adult female blue crabs twice since 2008, after exceeding it only once between 1990 and 2008. In 2021, the female blue crab population increased from 141 million to 158 million. However, it is evident that more needs to be done, since the number of juvenile crabs decreased to their lowest level since the survey began in 1990, and the dredge survey showed an overall drop in the blue crab population from an estimated 405 million to 282 million.

Although things are much better now than they were 50 years ago, more can be done to improve blue crab populations and the Chesapeake Bay as a whole.

Reducing harmful greenhouse gas emissions and adopting practices that keep excess carbon out of the atmosphere will help reduce climate change and its impact on blue crab habitat. Implementing forested stream buffers and green infrastructure can help mitigate weather extremes and improve water quality in the bay.

There are many things you can do at an individual level to help Maryland blue crabs and the Chesapeake Bay. Tell your state and local representatives that clean water is important to you. Urge them to support legislation that protects our waterways and habitat for wildlife, whether by phone or by attending a public meeting of local governing bodies. That goes for your U.S. representatives and senators too — call, write and visit, when you can, to show them what you truly care about. Take direct action by reducing pollution from your home, backyard, school or business. Recycle in your home to reduce the amount of waste heading to a landfill, avoid overuse of herbicides and pesticides in your yard that could run off into the water system, or host a litter pickup with a group of people.

However you decide to help, our state crustacean will thank you. By helping the Chesapeake Bay, we can ensure a healthy population of blue crabs to enjoy at picking houses for decades to come.